.

.

.

.

.

Below – The Village of Figget (Portobello) 1783.

1898 – William Baird’s Annals of Duddingston & Portobello – ... About the year 1763, a new settlement began to be formed in the parish at the mouth of the Figgate Burn, consequent upon the finding of a valuable bed of clay, and the starting of brick and tile making on rather an extensive scale by Mr William Jameson, (or William Jamieson?) an eminent builder and architect of Edinburgh. Mr Jameson having purchased forty acres of the Figgate lands, which at the time were a mere waste, covered for the most part with furze or whins, and commonly let to one of the Duddingston tenants for 200 merks, Scots — or £11 2s 2d sterling — began to build houses for himself and his workmen, and to sub-feu other parts of the ground for building purposes. The village of Brickfield or Figgate, as it was then called, grew with the progress of the various works, until by the end of the century there was a working-class population of about 300, with a few families of the better class, who had commenced to make it a summer residence, and had built several villas among the furze-covered sand hills …

… About the year 1763 – Mr William Jameson, the son of a celebrated Edinburgh builder, with a shrewd eye to the future possibilities of this barren uncultivated spot, began to look after it chiefly as a likely place for starting the manufacture of bricks. The estate of Figgate had been purchased a few years previous from Lord Milton by Lord Mure, one of the Barons of Exchequer, the whole seventy-five acres being got for £1600. Mr Jameson took off in feu about forty acres from the Baron at the rate of from £2 2s to £3 per acre per annum, and shortly afterwards (about 1765) found that underlying the deep drift of sand, which for the most part composed the soil of his property, there was a deep bed of excellent clay, most suitable for brick making. At the time referred to he was a young man about twenty-seven years of age, and had been associated with his father for nine or ten years in a number of important works then going on in connection with the extension and improvement of the city. The most important of these was the erection, in 1753, of the Royal Exchange, for which his father — Patrick Jameson — had the contract. At the laying of the foundation stone of this edifice by the then Lord Provost, George Drummond, there was a great Masonic demonstration, and young Jameson being anxious to take part in it, although under the prescribed age of admission to the Masonic fraternity, was out of respect to his father, admitted an apprentice In the Lodge of Edinburgh, St Mary’s Chapel, and took part in the procession. In the extensive operations connected with the building of the new town, Patrick and William Jameson had a prominent part. Large quantities of brick were required, not only to meet the home but the foreign demand and William set himself energetically to develop the resources of the lands of Figgate, hitherto so unproductive. According to the statement of Hugo Amot, the historian of Edinburgh, the “making of bricks in the vicinity of the city had begun about the year 1764 on a small scale, the number made annually not then exceeding 400,000.” But it went on increasing rapidly until 1779, the year in which the history was published when he says there were three brickfields in the neighbourhood,” the principal being at Brickfield or Portobello.” These works at the latter date were producing no less than three millions of bricks annually, which were not only used by the builders in Edinburgh, but were exported to Norway, the West Indies, Gibraltar, and North America. Excavations were first made by William Jameson for clay where Pipe Street and Bridge Street are now situated, and afterwards, he opened a pit in a field called Wallace Park, now forming the grounds of Mount Lodge, and had an extensive work in that locality. These works naturally led to the building of workmen’s houses in the neighbourhood of the works, and so we find that the older parts of the town are to be seen near to Pipe Street, and on the High Street in the neighbourhood of the Blue Bell Inn. The houses, many of which still stand in these localities, were certainly of the commonest description, generally built of brick and roofed with tiles. The bed of clay at Portobello, discovered by Jameson, is usually denominated as ”brick clay.” It receives this appellation because it is very suitable for the purpose of making bricks, in contradistinction to the boulder clay, which is itself a strong day, but greatly intermixed with stones, many of which are of very large size, as may be seen from some lying on the beach towards Leith which have apparently come from a distance, as they present the polish and groovings caused by much friction, and are generally pointed out as characteristic of the glacial period. The brick clay itself is not entirely free from stones. They are, however, comparatively few in number, and are generally of small size, but being often very hard they give no little annoyance in the working of brick-making machinery. The brick clay at Portobello extends from Joppa on the one hand to Craigentinny Meadows on the other and from the shore of the Firth of Forth a considerable distance towards Arthur Seat. The deposit of brick day has most likely been formed in the course of ages by the sediment brought down by the streams from the west, lodging in the locality. Hugh Miller, during the latter years of his life, when he resided in Portobello, carefully surveyed the clay excavations. In one of his published lectures, he has given a graphic picture of the mode in which he thinks the deposit of brick clay at Portobello was formed, from which we give a few extracts.

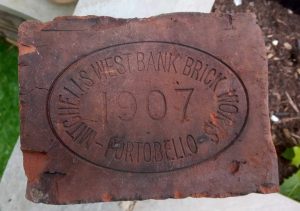

What are known as the Portobello brick clays occupy a considerable tract of comparatively level country, which intervenes between the eastern slopes of the Arthur Seat group of hills and the sea. The covering of rich vegetable mould which forms the upper stratum of the tract – so valuable to the agriculturist, that it still lets for about £6 per acre – precludes any exact survey of their limits; but we know from occasional excavations in the tract, and at least one natural section, that they extend over an area of at least a square mile. A well, sunk a few years ago at Abercorn Place, one hundred and ten yards on the upper or Edinburgh side of the first milestone from Portobello, passed through a stratum of the brick clays, six feet in thickness; and several excavations made in the immediate neighbourhood, on the farm of Mr Scott of Northfield, laid open the continuous bed which they form at various points fully a mile distant from the sea, where they averaged in thickness from five to seven feet. In all probability, judging from the general level, and their gradual thinning out, they terminate in this direction about the middle of the field which extends to the house of Willow Bank; while more to the south they appear about sixty yards below the mill of Wester Duddingston, in the section formed by the Figgate Bum, whence they stretch eastwards to near Joppa Quarry. They acquire their greatest elevation at Stuart Street and its neighbourhood [at Piershill] where they rise about eighty feet over the high water line; and attain to their greatest known depth in the town of Portobello at the paper works [Bridge Street], where at one point, immediately beside the bum, they were perforated several years ago in sinking a well to the depth of not less than 100 feet. Their extent along the shore to the west has not been definitely traced, but from their eastern extremity near Joppa, to where they terminate beyond the brickworks of Mr Ingram [Westbank], cannot greatly exceed a mile. The boulder clay appears all around the edges of the area which they occupy, and forms I cannot doubt, the basin in which they rest. It appears in a characteristic section a little above Duddingston Mill, charged with its grooved and polished boulders; it was cut through to a considerable depth by the excavations for the North British Railway, in the vicinity of Stuart Street and Abercorn Place, and there found underlying the brick days; and it appears along the shore, accompanied by some of its most striking phenomena, both to the east and west of Portobello, a little beyond the limits of the basin. In short, the Portobello brick days may be regarded as occupying a boulder clay basin or valley about a mile in length and breadth, not reckoning on their unknown portion, which seems to extend outwards under the sea; and, thinning out all around the edges of the hollow, they attain, where deepest in the lower edges of the Figgate Burn a thickness of at least a hundred feet.

Hugh Miller found in the Abercorn Works a bed of shells of the Scrobicularia Piperata, which is chiefly to be found at the mouths of rivers or inlets, not remote from freshwater; also at a lower stratum scattered specimens of the common periwinkle and a few much-wasted valves of the crimson tellina. Besides these the trunks of trees – the oak, the Scotch fir, the birch, hawthorn, and alder – along with reeds and water flags. The place held by the brick clays of the entire Portobello deposit, in relation to the Arthur Seat group of hills, and their probable derivation from the boulder clays of the district is not unworthy of being noted. Continuing, Hugh Miller says:- ” The entire deposit furnishes us with two little bits of the picture. We are first presented with a scene of islands – the hills which overlook the Scottish Metropolis, or on which it is built – half sunk in a glacial sea. A powerful current from the west, occasionally charged with icebergs, sweeps past them, turbid with the washings of the raw, recently formed boulder clays of the great flat valley which stretches between the Firth of Forth and the Clyde; and in the sheltered tract of the sea to the east of the islets, amid slowly revolving eddies, the sediment is cast slowly down, and layer after layer, the brick clays are formed along the bottom. And then, in long posterior ages, after the land has risen – all save its last formed terrace – and the subarctic rigour of its climate has softened, we mark a long withdrawing estuary running along what is now the valley of the Figgate Burn. It is skirted by the aboriginal trees of the country – oak, and birch, and alder, and the Scotch fir; and, save where the sluggish stream creeps through the midst, we see it thickly occupied by miniature forests of reeds and rushes, amid the intricacies of whose roots the mud-loving scrobicularia breed by thousands.” From these pictures of antediluvian times, we return to a consideration of the application which human ingenuity has made of the materials so bountifully supplied by nature. To this splendid bed of clay, Portobello is largely indebted for any manufacturing and commercial prosperity it has enjoyed. It was certainly the one industry – the converting of this clay into bricks, tiles, etc., which attracted to the Figgate Whins a gradually increasing population of workmen, and led to the starting of other industries, and at length to the formation of a community composed of all ranks and classes, from the Peer of the Realm to the commonest hodman.

Willam Jameson’s works proved to be thoroughly successful. The demand for bricks was large, and being near to Edinburgh, where an extensive building was then going on, these could be furnished by him at the lowest prices. After a few years the supply of clay in the neighbourhood of Pipe Street, though far from being exhausted, ceased to be wrought to the same extent. The Pipe Street work was then leased by Jameson to his clerk, Mr Morton, and the brickwork at Mount Lodge was opened. The roadway to the latter, now Windsor Place, was originally named Nicholson Street, after Mr Jameson’s wife, who was a daughter of Sir William Nicholson of Tillicoultry and Jarvieswood. In all likelihood, its name was changed to ”Windsor Place” in commemoration of the visit of George IV. to Portobello in 1822, as being more pleasing to the aristocratic families who resided in it then. In 1767 Mr Jameson built for himself what is described as a “handsome dwelling house” which he called Rosefield, still standing in Adelphi Place. At that time it faced the main road, or High Street, had a garden or shrubbery in front, with a carriageway to the street, and an extensive and beautiful park in the rear, through which flowed the pure waters of the Figgate. This he made his summer residence, his townhouse at that time being in Turk’s Close; but in the latter part of his life, he resided entirely at Portobello. With a view to utilising the ground occupied by his first brickwork on the opposite side of the road for feuing purposes, he set about filling up the excavations there made, and a story is told of him that having got a large contract to construct the drains of the new town of Edinburgh, he determined to use the rubbish for this purpose. By the agreement into which he entered with the Town Council, he was to have the privilege of carting all the superfluous rubbish to Portobello without paying the usual toll- bar dues at Jock’s Lodge. The tollkeeper, perhaps considering that the number of cartloads exceeded all reasonable bounds, one day closed his gate and refused to allow the carts to pass without the usual toll. This was reported to Mr Jameson, ‘ Weel, weel,” said he to the carters, “just coup your carts at the toll-bar.” This was accordingly done and caused so much annoyance to the tollkeeper and the public that no further interruption was made, the tollkeeper being only too glad to get rid of the nuisance. In this way, Pipe Street was formed, and afterwards feued off to builders. It got its name from the fact that the water supply for the use of the inhabitants was brought thither from the burn where it was pure and uncontaminated above Mr Jameson’s house, in several large pipes, which being carried underneath the High Street, discharged themselves into a large trough at the east end of the cross lane between Pipe Street and Bridge Street, or as it was then called “Tobago Street.” The greater part of the buildings erected in this neighbourhood were chiefly for the workmen connected with the brickworks; but after the erection of Mr Jameson’s “handsome dwelling house,” it seems to have occurred to some of the Edinburgh people that the locality was not without its attractions as a summer resort for their families. The wild uncultivated sand downs, with their covering of golden furze and broom, began to be enclosed. Little farms, such as Rabbit Ha’, Middlefield, and Portobello Park, afterwards Park House, with their one-storied, red-tiled offices, sprang up at some distance from each other, surrounded with their little patch of grain and dairy pasture; and the soil, if somewhat light, was found to be productive. The air of the place was fine, and if not so pleasant in spring during the prevalence of the east wind, it was bracing and wholesome during at least nine months of the year. Above all, the beautiful level sands, free from rocks, gravel, or shingle, and with no dangerous sandbanks or shoals, were recognised as most suitable for sea bathing. We accordingly find that between the years 1770 and 1780 a few superior residences were erected on the lands of Figgate, being sub-feued from Mr Jameson. These, in some cases, included several acres as parks or pleasure grounds, which were enclosed with high substantial walls, built for the most part of boulder stones, which were then plentiful all round, and topped with a few courses of brick. A few of these curiously built three-storied walls may still be seen amid the closely compacted modem buildings which now hem them round, as in Ramsay Lane, Rosefield Avenue, and at the top of Pipe Street. In all probability, the lower or boulder-stone portion of these walls would be all that was at first required to fence the properties, the courses of brick being afterwards added to give more security or seclusion. Among these original villas (which for the most part were built of brick) may be mentioned Ramsay Lodge, Mount Charles, Shrub Mount, Jessfield, and the Tower, surrounding which were large orchards of fruit trees where, the Old Statistical Account tells us, ”the apple, pear, plum, and apricot flourished in great profusion.’ Ramsay Lodge took its name from General Ramsay L’Amy, a West Indian veteran, who after having served in Jamaica for many years, came to reside there. It occupied the centre of a spacious park and garden. Originally its principal entrance was by a large iron gateway in Ramsay Lane, close behind the present Municipal Buildings. Long afterwards, when each side of the lane near the High Street got to be filled with mean cottages and other buildings, a new entrance was opened from Bath Street about 1831, having an avenue of trees, and a porter’s lodge. At the beginning of the century Ramsay Lodge belonged to Mr Spottiswood, from whom it passed in 1830 into the hands of Mr James L’Amy, Sheriff of Forfar, until about 1848, when it became the property of the late Mr Bobert Mercer, W.S., since whose death in 1870 the garden and park have been feued and built upon, and the old brick house has fallen sadly into decay.

A strange story is told of General Ramsay L’Amy, its first owner, to the effect that when in Jamaica he was engaged to be married to a young lady residing there. During an epidemic then raging in the island, the young lady having taken yellow fever, he was horrified on calling for her one day to be told she was dead and had been laid out in an upper room for burial. Desiring to be allowed to see her once more, he was strongly dissuaded from it in case of infection. He pressed the matter however and was allowed to go upstairs, taking a small flask of brandy with him. The young lady, now quite black, had all the appearance of death, but on touching her cheek the General thought he discovered signs of life. He moistened her lips with the liquor. She made a motion of returning consciousness, opened her eyes, and finally sat up. Strange though it may seem, she speedily recovered, and was shortly afterwards married to the General, and came home to spend the evening of her days with him at Ramsay Lodge about the year 1780. Mount Charles, a quaint picturesque building, also of brick, standing within its own grounds, was built by Mr John Dickson, W.S., of Robbiewhat, Dumfriesshire. The greater part of the original building was removed some thirty-six years ago to make room for the present elegant mansion and was long occupied by his son, Mr David J. Dickson, wood merchant in Fisherrow. He was the Provost of the town from 1840 to 1843. Shrub Mount, many years after known as The Tower residence of the lamented Hugh Miller, and the place where he ended his life, was probably built by Mr James Cunningham, W.S; it was long occupied by Mr Wm. Creelman, one of the first lessees of the Abercorn Brickworks. When it was built, about 1787, it had extensive grounds attached, including the whole area now occupied by Tower Street, and the houses on each side of it down to the sea. Within this area, there was a hill of considerable height called the Bleaklaw, the highest point in the landscape, from which an extensive view of the surrounding country could be had. In Hugh Miller’s time, the top of this hill was adorned with a fine clump of trees, but since the grounds have been cut up for building purposes, much of the hill has disappeared, as well as the trees. It was situated immediately to the rear of the publishing premises of Messrs Thos. Adams & Sons. But perhaps the most extraordinary building of its day was the “Tower,” erected in 1785, some say by Mr Jameson, some by Mr Cunningham, as a summer house on the shore, the probability being that it was built by Mr Jameson for Mr Cunningham. In its erection he displayed the most eccentric taste, the materials and the style adopted being original and fantastic. It was built partly of brick, octagonal in form, four stories high, and a mixture of every conceivable style of architecture. Stone and brick were used indiscriminately for ornament, but most of the mullions, cornices and other ornaments were old carved stones, some of which, it is said, belonged to the old Cross of Edinburgh, some to the Cathedral of St Andrews, and some, probably added afterwards, from the old College of Edinburgh, which in 1789 was removed to make room for the present University buildings. A few years afterwards Mr Cunningham got into monetary difficulties, and in 1806 ‘the property was sequestrated and sold. The Tower was advertised for sale in the Edinburgh Oourani of 11th April 1807 in the following terms:- ” To be sold by private bargain, the Tower at Portobello, with the adjacent buildings. The Tower is situated on the shore at Portobello and commands one of the finest views in the kingdom, and the sea beach is well known to be the finest in Scotland for cold bathing. About 100 feet or more of ground on the west can be taken in from the sand at a very small expense, which would be exactly on a line with the other grounds lately taken from the sea, and the walls of the adjacent buildings are sufficiently strong to admit of other two stories being added, which might be made to communicate with the Tower and form two elegant and commodious dwelling houses, each having a proportion of the Tower.” … ”The premises will be shown by Mr Turnbull at the Tower.” We are not aware that it was purchased by anyone at this time; we are rather inclined to think it was not. A daughter of Mr Tumbull was subsequently married to Mr Jameson’s son, and through her, the Tower became the property of the Jamesons. At the beginning of the century it was let to summer visitors, but after a time was allowed to fall into neglect, and ultimately it had become a complete ruin. In this condition it stood for many years — its roof fallen in, its windows broken, its joists and rafters rotten and lying in a broken heap on the ground floor, with its circular stone stair broken here and there, and impassable except to venturesome boys in search of jackdaws’ nests— during which time it seems to have been in the hands of Jameson’s heirs, whose property it was in 1834. Thus it stood till about 1864, when Mr Hugh Paton, the publisher of Kays Edinburgh Portraits, having purchased the property, built the present commodious mansion adjoining it, and completely restored the Tower to its original condition, making it a part of his residence. The Tower is the scene of rather a weird story, written some sixty years ago, called the “Wizard of the Tower.” Some of its old carved stones are very curious, we give by way of illustration an interesting old sundial which originally stood at the west gateway, fully ten feet high; and a heterogeneous group of carvings in front of the building, where may be seen the figure of an angel minus the head, and several monograms.One stone bears the date 1674. The Tower is now the property of Councillor Wm. Gray. Jessfield, Rosefield Cottage, and Williamfield, on the south side of the High Street, were all built towards the end of the century on ground sub-feued from Jameson’s extensive park adjoining his own house; Rosefield Avenue being formed as a convenient access to these houses, or more probably before their erection, for strangely enough in Taylor & Skinner’s Survey Map, published in 1776, Rosefield Avenue is the only street indicated in the locality. Though these detached dwellings, with smaller ones here and there, were dotted over the otherwise desolate scene, the place up to this time was practically only a scattered collection of dirty workmen’s cottages; clay holes and brick kilns being the principal features of the landscape in the neighbourhood of the bum. Jameson’s property lay all to the east of the burn but the value of the clay-bed he had discovered speedily stimulated the proprietors, of the estates west of that boundary to open up their ground also. Mr Miller of Craigentinny accordingly offered facilities for brick-making on his property, on the north side of the highway, while the Marquis of Abercorn gave a lease of a large field (called Adam’s Laws) on the south side to a Mr Hamilton, by whom it was opened as the Abercorn Brick and Tile Work. This extensive work, in the hands of the Creelmans, the Livingstones, and of late of Messrs Thornton & Co., has since been successfully carried on for over a hundred years. It is now in the hands of Messrs Turners, Limited. Perhaps the earliest brickmaker on the Craigentinny Estate was Anthony Hillcoat, a bricklayer from Newcastle. He got a lease of Westbank where he commenced to make bricks with what are called clamp kilns, i.e the bricks after being dried by exposure to the weather are set with alternate layers of small coals, and burnt until they are quite hard. He built the older part of Westbank House (since demolished) as his residence. Adjoining his works two brothers had acquired a lease of ninety-nine years of Rosebank, where they started a red paint or “keel” work, and a brickwork. An atmosphere of suspicion seems to have hung for long over these men among the older inhabitants of the place, which has been even-handed down to our day, some strange stories being whispered of the conduct of the brothers, Edward and Alexander Colston, “the bloody Neds.”

In 1781 the Colstons erected a house adjoining Westbank on the east side of the “Private Lane,” which their mother kept as an inn. As the story goes, though we will not vouch for its accuracy, this seems to have been an infamous nest of desperadoes. For though the brothers professed to make bricks and paint, it was commonly believed that their real occupation was that of highway robbers, and suspicion rested pretty strongly upon them for various daring acts of robbery, and even murder. At all events, Sandy Colston and “Bloody Ned” were for long a terror to the neighbourhood. Whether the designation “bloody” was attached to Ned from a suspicion of his being implicated in foul play, or from the fact of his hands and clothes being discoloured with the red paint, we cannot say, but the locality of their “works ” bore anything but a favourable reputation, and few persons of respectability would risk passing the vicinity of the Portobello “keelies” after nightfall without an escort. One old man, since dead, used to tell that when he was a lad running about the hillocks, with which the neighbourhood then abounded, jumping down from the top of these one day he was horrified to strike upon the body of a man, buried only a little beneath the surface of the sand. It was supposed to have been, rightly or wrongly, that of some unfortunate traveller who had fallen a victim to ”Bloody Ned.” Notwithstanding all the suspicion that hung about his character and conduct, Ned Colston lived to be an old man, and his son, who was a capital singer, became afterwards the precentor in the Chapel of Ease, built in 1809. Other works besides those for the manufacture of bricks and tiles now sprung up, for the brick clay was found capable of being manipulated with finer imported clays in the construction of brown pottery and whitestone ware. About the year 1786 two potteries for the manufacture of earthenware and porcelain were built, one by William Jameson and the other by Anthony Hillcote, near to the mouth of the burn at the foot of Pipe Street and Tobago Street. In the former, now the property of Messrs Alex. Gray & Sons, a firm of the name of Scott Brothers started an extensive work for the manufacture of earthenware. Their dinner and dessert services were said to be of very superior workmanship, being ornamented with yellow designs, leaves, and even grotesque figures painted on a chocolate ground. They also made mantelpiece ornaments – figures of fishwomen, dock stands, candlesticks, etc. This ware is, we believe, still highly prized by connoisseurs, chiefly no doubt on account of its scarcity, and brings a high price in the market. Some specimens are to be found in the collection of Lord Mansfield, and some at Dalkeith Palace in the possession of the Duke of Buccleuch. It did not, however, prove a financial success, and after six or seven years its manufacture was discontinued. In 1795 the work was taken up by Messrs Cookson & Jardine for at least some fifteen years and was afterwards continued by Mr Yule and then by Mr Samuel Rathbone. To meet the requirements of the growing trade of the place, and with an enterprise truly commendable, betokening his entire confidence in its ultimate success, Mr Jameson, about the year 1787 – 1788, projected the erection of a harbour at the mouth of the Figgate Burn. The import of coals and whiteware clay from Cornwall for the potteries, and other commodities was now considerable, while the export of bricks, tiles, etc., was also increasing so that the prospects of a harbour being needful and likely to pay the outlay necessary for its completion were not unreasonable. Hitherto sloops, brigs, and other small craft bringing or taking away goods had to be beached in order to receive or discharge their cargoes, which on an unprotected shore was not always possible or safe. Accordingly, on the spot made memorable by the landing of the English fleet in 1560, with their ”great artailzerie and ordinance ” for the siege of Leith, Mr Jameson resolved to erect a harbour. The contractor employed by him was Mr Alexander Robertson, the lessee of Joppa Quarry, who undertook to cart to the harbour a thousand loads of boulder stones, in addition to the large squared stones necessary for facing the pier and harbour walls, but the work appears to have been carried on under his own immediate supervision. According to a statement by Dr D. M. Moir in his Roman Antiquities of Inveresk, the boulder stones for the harbour were taken from the old Roman Road between Magdalene Bridge and Joppa. The pier, with a rough kind of breakwater in front of it on the east side of the harbour, was carried out in a northerly direction directly from the foot of Pipe Street. The entrance to the harbour was narrow and the basin small, and certainly it would not accommodate more than three or four small vessels at a time. On the east was the ‘ harbour green,” which did duty as a dockyard. On the west side the sea wall took a turn from facing the north inwards towards the burn, and was built in a substantial manner; but years of neglect, and repeated inroads of the sea, soon told upon the work. Some forty years ago a great part of the harbour was in existence. The pier was in ruins, but the harbour walls were still entire, though the basin was almost silted up with sand, only sufficient water being left to make it a favourite resort of schoolboys for sailing their toy boats. The remains of the pier and eastern bulwark may still be traced among the heap of stones scattered on the beach, but not a vestige remains of the harbour. It has entirely disappeared. Even the very site can with difficulty be traced, as the greater part of Messrs A. W. Buchan and Coy.’s pottery is now built over what was the old harbour basin. Amid the rains may still be found stones that have done duty elsewhere, old steps, mullions, and pediments of doors or windows, and even pieces of broken Gothic pillars. These are supposed to have formed part of the old college of Edinburgh and other buildings near the South Bridge, which were demolished in 1789 to make way for the present University buildings. At the time the harbour was built there were several other works in its neighbourhood besides the potteries referred to. In Tobago Street, a flax mill had been opened, and further down a soap work. The motive power for these mills was supplied by a lade from the burn, which ran down the east side of the street in an open mill race, till it reached the foot, where it crossed through the ”Trows “(now the Slaughter-houses) into what was called ”Tibbie’s Hole,” then into the harbour. In its course to the harbour, it drove several water wheels for the flax mills and potteries …

Below – 24/05/1790 – Caledonian Mercury – Advert for Brickfield, Figget Bridge – William Jameson. Reference to David Craik and William Christie.

1799 – Scottish East Coast Potteries 1750-1840 by Patrick McVeigh – It is sad that so little is known of Hilcote and his work and, since there is no physical trace of the Figgate Pottery, our knowledge will probably remain fragmentary, but we do know that Samuel Hilcote, his son, was in 1799 involved in what was now the almost inevitable litigation over brick and tile making. In this case, it was not Hilcote’s landlord Miller who was the prosector but the ever-watchful William Jameson. In the proceedings, ‘Jameson V Hilcote at Brickfield’, Jameson alleged that the Hilcotes were using clay to which he, Jameson, had the exclusive rights. The contest was an unequal one, for very often the litigant in proceedings such as these knew very well that although the case was not a strong one, the finances of his opponent were weaker still. After 1800, Hilcote’s Pottery vanishes from the scene and the area, as we have noted, was eventually to become a brickworks on a large and prosperous scale. Thomas Hilcote, son of Antony senior, shortly after the closure of his father’s property went into partnership with Rober Hay. making bricks at Westbank. This was still on the land of the Figgate but well to the westward of the wrathful Jameson …

08/06/1830 – The Edinburgh Gazette – Reference to William Jameson, Brickworks, Portobello in a notice to the creditors of Andrew Ramsay.

04/12/1896 – Also referred to in the Portobello Advertiser.