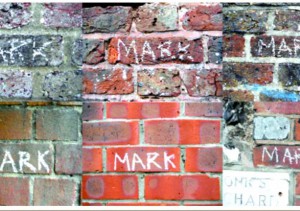

With regards to Scotland, bricks began to be marked around the early/mid 19th century.

These marks would bear the manufacturer’s name or perhaps the brickworks site owner’s name, their initials, the name of the brickworks or place of manufacture or indeed any combination of such.

The year of manufacture was often stamped also.

Such stamping of these bricks was one of the earliest forms of advertising on a large scale.

.

Below – Gilchrist & Goldie, Old Langside Road, Glasgow, 1866.

The above was the same for building bricks as well as refractory bricks.

However, as the quality of refractory bricks was refined and manipulated through technical and composition changes then new marks began to appear. Refractory bricks began to be marked with additional letters, numbers and words.

Refractory bricks began to be marked with regard to their chemical composition and content. Refractory bricks were made from high-quality clay comprising of different percentages of chemical constituents eg Silica, Alumina, Kaolinite, Mullite and Bauxite.

Below – Stein Mullite

Below – Kaolinit

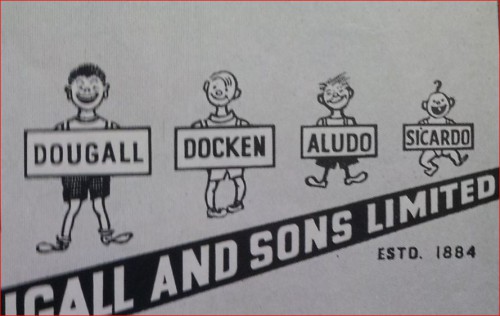

Then there are combinations such as chemical and manufacturer.

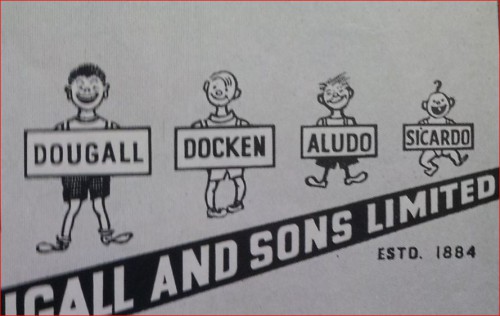

Below – Aludo – which appears to be a combination of Alumina and Dougall (the manufacturer)

Below – Similarly – Sicardo – Silicon Carbide and Dougall.

Below – Stein 73 – which refers to the Alumina content being at least 73%.

Below – Some refractory manufacturers marked their bricks with the customer’s name or initials.

Below – James Dougall marking a product Coppee for the Coppee Coke Co of Gracechurch Street, London.

Below – Stein marking their trademark Bluebell bricks with WD for Woodhall Duckham.

Below – Various Scottish manufacturers marking refractory bricks with initials that are believed to stand for numerous South American Railway companies.

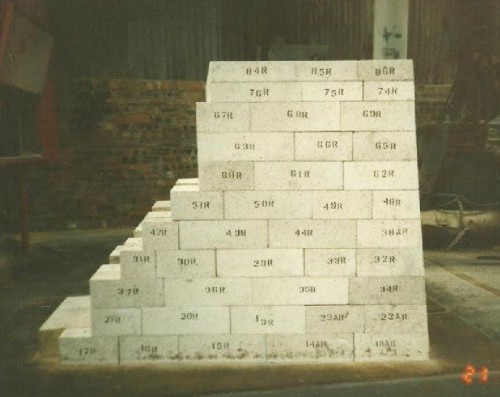

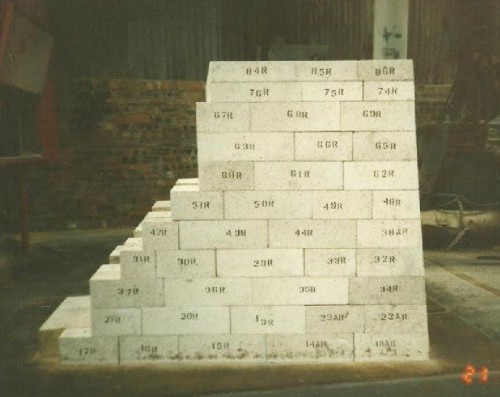

Some refractory bricks and specials were marked with a code that tells a furnace builder etc where, in the furnace, (kiln, stove, boiler etc) they should be placed.

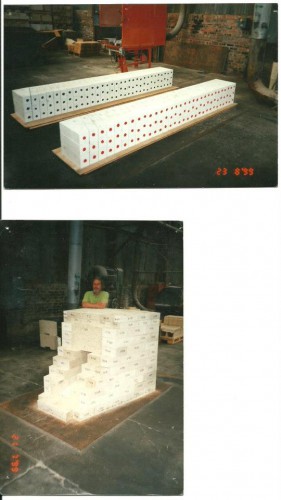

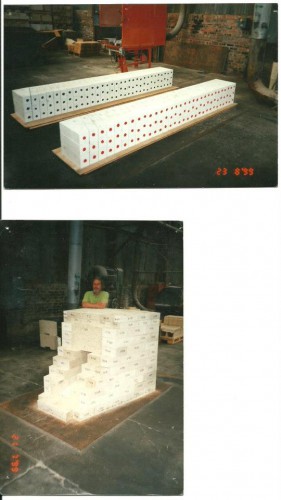

Below – Refractory bricks at the Manuel Works, Linlithgow are stencilled giving each brick a positional code.

Mark Buchannan, a former employee at the Manuel works states “Codes were used to identify different shaped bricks according to customer specs and would be used to assist with their placement when being built. When we dealt with large orders with lots of variations, the code would be abbreviated and stencilled onto each brick eg BS – Bethlehem Steel in the USA, HS – Hoogovens in Holland and CS – China Steel from China”

Below – This template below would be used to check brick shapes and once confirmed that they were the same as the template (there were often only subtle differences between special shapes which were hard to identify by eye) then the bricks would be marked with a stencil as per the mark on the template. Harry Baird states –

The code is

BH – Bethlehem Steel (USA)

HH – Sill 66

229 – design number.

Below – All bricks that required size banding were done by hand except the chequers in the latter years that went through a machine which sprayed them with the appropriate colour. The colours represented tolerance settings dictated by what the customer wanted.

.

*****************************************

Harley Marshall, formerly of the Stein Castlecary Works, Bonnybridge recalls that Nettle A and Nettle B firebricks were ‘trial’ bricks. They were both made from the same clay with 42% alumina but they were experimental in other compositions and firing. He recalls such bricks sitting wrapped in brown paper in the laboratories awaiting examination etc.

He also states that many of Stein’s bricks were marked with 3 or 4-figure numbers. These represented orders or customer identification but often they simply related to a page in the order book and thus related to a single and were thus easy to look up if a customer complained or queried the order. The customer simply stated the number on the brick and someone back at Stein’s would flick through the order book to the correct page and take it from there.

Below – This example certainly confirms that order numbers were stamped on fire bricks by Stein.

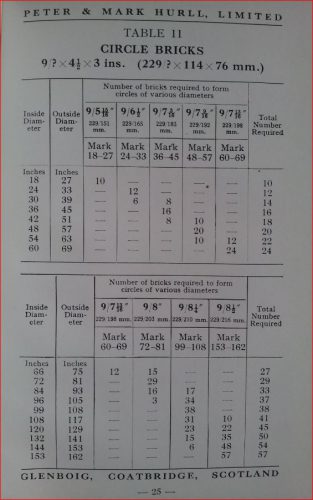

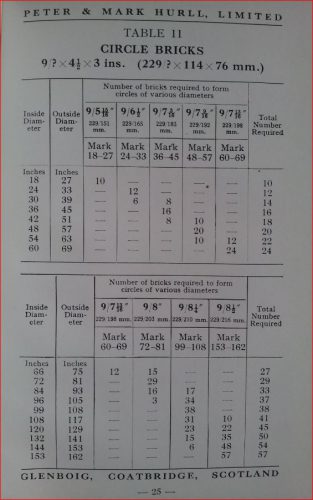

He also clarified why some bricks are marked eg 72 – 81 or 105 – 114 with the difference being usually, but not always 9. Such bricks were curved and were called circle bricks as they would join together to form a circle and thus were used in chimney construction. The numbers related to the inside and outside diameter of the chimney measured in inches. Thus 72 -81 meant the finished chimney would have an internal diameter of 72″ and an external diameter of 81″. The difference was usually 9 as normally bricks with a 4½” width were used … and across the external diameter there would be 2 bricks thus 2 x 4½” and thus making the difference of 9″.

Below – Similarly, it appears some companies only added one set of numbers to their brick eg Castlecary 72 (Weir) and Atlas + A 72- and I suspect that relates to the internal diameter of the finished chimney only.

.

Below – The following products were found on a waste dump ground adjacent to Dalzell Iron and Steel Works and Ravenscraig Steel Works, Motherwell. They bear the numbers 9170 or 9172. They are all completely different so the numbers are unlikely to refer to the shape or design. The numbers are very likely to be order numbers – so perhaps 9170 was stamped on all the bricks required to complete a project at either steel works and similarly for 9172. They could be a customer number too eg 9170 for the Dalzell Steel Works and 9172 for the Ravenscraig Steel Works but an order number is more likely.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Below – This stamp ‘9435 Thistle 2 D A 6’ is the same shape as the brick above ‘9170 Thistle 2 D A 6’ ( The photos are taken at different angles) – This corroborates the evidence that the 9170 or 9435 do not denote the design shape and is far more likely to represent an order number.

********************************************************************************

The explanation by Harley Marshall regarding the markings on the chimney bricks has also been confirmed by the finding of a Hurll firebrick catalogue.

*******************************************************************************

John Bramall, formerly of GR-Stein and based in England states that the company made bricks marked Selfrac 23, 26 and 28 and recalls that the 23, 26 and 28 referred to the service temperatures in Fahrenheit – i.e. 2300, 2600, 2800.

One story of interest concerns the firebricks of John Stein and one of James Dougall & Sons. Stein had a range of refractory bricks which he named after plants – Nettle, Thistle, Myrtle, Daisy and Bluebell. Nettle branded bricks were sold all over the world and in huge numbers. The story goes that James Dougall manufactured a firebrick and called it Docken. He marketed it directly to try and impact on the popularity of the Nettle brick. You will know that Docken leaves can be used to reduce the swelling caused by a nettle sting – The trademark Docken was chosen deliberately as it was hoped it would take out the sting of having to pay the cost of a Nettle brick which was a much dearer option than buying a Docken brick.

There are also purely accidental marks such as fingerprints, boot prints and animal prints. Some people are of the mindset that finger and in particular thumbprints on bricks were done to authenticate the brick as being handmade. I do not subscribe to this theory. The bricks were handled from the moulds onto the drying floors and then again when being moved to the kilns for firing. As such the clay was still ‘wet’ and quite simply the thumbprint which is normally seen to the top right of the brick was an inevitable mark left behind when handling a damp clay brick.

.

.

.

There are many refractory bricks with added numbers and letters that still remain a mystery.

Some bricks were simply marked at the whim of the moulder or someone else involved in its manufacture.

Below – This one for whatever reason was inscribed by using something similar to a nail or stick and with the word ‘Thur‘

Others were marked with symbols.

Below – a simple cross marks this early refractory brick. Perhaps it was an individual moulder’s mark and used to help tally his daily production and keep his bricks separate from a fellow moulder who perhaps used a square as a marker?

.

**************************************

Harley Marshall, who worked for JG Stein between 1949 and 1991 and finishes his career at the Manuel Works as Export Sales Manager also states that Stein products were sold to the Admiralty for use in ships boilers. The Admiralty would send in orders and these orders would be marked with the order number. Generally, they were marked AP then a 2 or 3 digit number. – AP11 – AP stood for Admiralty Pattern.

These boiler bricks had a flanged and recessed hole which did not go all the way through the brick. A special bolt with wide flanged wings on the head was entered into the recess and twisted until the wing were being and within the brick itself. The bolt was then fed through the boiler wall and tightened from the outside pulling the brick onto the boiler wall. The brick on the inside of the boiler thus was solid with no bolt heads showing.

*************************************

Harley also states that Stein firebricks marked 84P were used in the Aluminium production industry. These bricks had ‘non-wetting’ properties so the aluminium did not soak into them.

The 84 stood for Alumina content and the ‘P’ is believed to have stood for Phosphate bonded.

************************************

Liptak and Detrick brickmarks – Harley tells me that Stein used the Liptak and Detrick designs and manufactured identical products however due to the 25-year patent on these products as registered by Liptak and Detrick, Stein had to pay a royalty on every one of these specials and stamp them with either Detrick or Liptak.

Liptak – Bigelow-Liptak Corporation was originally incorporated in 1927 with the merger of the Bigelow Arch Company of Detroit and Liptak Firebrick Arch Company of Minneapolis, as a direct subsidiary of A.P. Green Refractories Company. Bigelow-Liptak of Canada was incorporated in Toronto in 1940, as a subsidiary of the Corporation.

M. H. Detrick – The M.H. Detrick Company is a heat refractory manufacturing company, based out of Mokena, Illinois. The company primarily sells suspended refractory constructions and industrial heat enclosures to various businesses. Founded in 1925, the M.H. Detrick Company started in Illinois as a heat enclosure manufacturer. Although the company began as a relatively small business, it quickly became an industry leader in heat enclosures and began adding various heat enclosure products to its lines, such as refractory linings and steel.

Examples of Liptak

Example of Detrick

Examples of Bigelow

*************************************************

Many bricks are shaped – feathered, wedge etc and I believe that the number stamped on the brick is a simple reference to the angle of the feather or the taper and not necessarily the angle in degrees. It could be a code. eg ETNA No1 could refer to a brick with a 15% taper, ETNA No 2 to a brick with an 18% taper etc.

************************************************

Harry Baird used to work at the Manuel Works, Linlithgow. It’s somewhat confusing but a particular brick with say 50% alumina content may have an international code and also a specific code as per the individual manufacturer. He gives the following as examples of brickmarks and what they could mean.

ROXX 144 ND

RO – code for a specific design or customer. His recollection is that RO stands for the customer in this example and he recalls it may be The Gary Works, a major steel mill in Gary, Indiana, on the shore of Lake Michigan – WIKI

XX – signifies an International standard for Alumina content.

144 – Code for where the brick fits into the design/structure plan in question.

ND – Nettle Dense.

And again

Below – CBHS 130 – He remembers this as possibly being a special design for a glass tank project.

CB – code for a specific design or customer.

HS – signifies an International standard for a brand or type of brick and in this case, he believes it was for Sill 63 or Sill 66 bricks.

130 – Code for where the brick fits into the design/structure plan in question.

Below – The above is corroborated in part by this photo of a pack of bricks heading for Holland.

and again

RCHH 112 SCR

RC – code for a specific design or customer

HH – signifies an International standard for SILLMAX 66

112 – Code for where the brick fits into the design/structure plan in question

SCR – Stein code for Sillmax 66 brick

*********************************************

John Bramall recalls – RCHH – is a code for – RavensCraig Hoogoven’s design of Hot blast stoves – hence RCHH. Hoogovens were the Dutch steelworks in Ijmuiden (later part of Corus, now Tata Europe) that in the 1970s had developed and patented an energy-efficient and technically good design of hot blast stove lining for existing hot blast stoves that needed relining. GR-Stein had a worldwide licence to supply refractories to the Hoogovens design. SCR – Sillmax Super Creep Resistant

In the Sillmax SCR product listings, there were also PAHH and COHH – these will be shapes for other Hoogovens design Hot blast stove projects. You would have to look at the documents to see which steelworks they refer to – they won’t be in the UK. I think it was POHH for Port Talbot, ACHH for Acominas (Brazil), AHHH for Ahmsa (Mexico), HOHH for Hoogovens themselves.

Sillmax SCR was used in the hot blast stove outlet area. It’s likely that shape RCHH 112 would not have been supplied in any other quality/brand unlike the shapes used in stove walls or in the combustion chamber walls or in the chequerwork. Silica was used in the top of the stoves in the domes and the uppermost part of the walls.

RC – customer code – in this case Ravenscraig but could be many other 2-letter combinations

HH – Hoogovens design of Hot Blast Stove

112 – brick shape or position mark in the construction design

SCR – Sillmax SCR – SCR means Super Creep Resistant

Between 1975 and 1983 when I worked at GR-Stein and was involved in the Ravenscraig Hot Blast Stove rebuilds using the Hoogovens internal combustion design, the SCR product got its super creep resistance by being fired twice through one of the basic brick tunnel kilns at Manuel Works.

I think that Stein 73D bricks used a similar twice-fired process during their manufacture.

The basic brick kiln schedules were of higher temperatures than those of the High Alumina and Firebrick plants.

Sillmax 66 was not manufactured at that time. After basic brick production was moved from Manuel Works to Worksop Works I suppose the Manuel made bricks would be fired twice through the Manuel Works High Alumina kilns, perhaps to a higher firing schedule. Maybe this brick was then named Sillmax 66?

The SCR product was a GR-Stein product as Sillmax was a General Refractories Group brand that after the merger with John G Stein was manufactured by GR-S at Manuel Works.