There is little doubt that James Young made bricks to construct his employee’s houses etc and also exploited the fireclay seams to make refractory bricks for his numerous enterprises – but did he mark them.

See Young’s and Young which appears to be a different Company. (Note – SBH – Young and Young’s have both been found on-site at the Heathfield Fireclay Works so I am fairly confident that they are both products of John Young and Son who at one time operated the works there).

Young’s Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company Limited, Addiewell, Linlithgow – Founded in 1866 to exploit the shale fields of West Calder, this company purchased the Addiewell shale oil site from James ‘Paraffin’ Young (1811 – 1883) who took very little active interest in the company, though he held shares in the company and sat on the board.

“1866 is noted as being the year in which the much heard of Young’s Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company came into existence. It was started with a capital stock of £600,000, of which £400,000 was paid to Young for his Bathgate and Addiewell Works, together with the leases of the shale fields &c., while Young retained a large holding in the company, and acted on the board of directors. Although the company was fairly prosperous for some years and had an output equal to about one-third of the total production of the Scotch works combined, it cannot be said to have been a financial success of late years; due, firstly, to it having been handicapped, as a large dividend payer, by the burden of carrying an excessively large capital, and secondly, being the first company of any importance, the works were necessarily fitted up with expensive apparatus and machinery that proved in a few years to be unsuitable for refining the oils so as to suit the more exacting requirements of the later-day trade.” (A Practical Treatise on Mineral Oils and their By-Products, I. Redwood, 1897)

By 1868 the company-owned sites at Bathgate (which had a crude oil refinery and acid plant) and the larger Addiewell site, and employed 1500 people and processed 172,000 tons of shale per year. In 1879 the company expanded by buying the West Calder Oil Company, although the Bathgate site began to slow down. In 1884 crude oil production ceased at Bathgate, and by 1887 the process plant had transferred to Addiewell as well, although the sulphuric acid plant operated until 1956. The company acquired the Uphall Mineral Oil Company Limited in the 1890s and gradually concentrated its operations at the Uphall works to exploit the shale field there. By 1902 the company had acquired a coal mine at Baads, several local farms, and owned a lampworks in Birmingham.

Scottish Oils Limited

Scottish Oils Limited was formed by the merger of the 5 remaining Scottish shale oil companies (Pumpherston, Broxburn, Oakbank, Philpstoun and Youngs) in 1919. This company was a subsidiary of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (which became British Petroleum in 1954), although all five companies continued to operate independently within the structure. Based at Middleton Hall, a 1707 mansion house in Uphall, Scottish Oils provided admin, marketing and technical support for the Scottish shale oil industry. Its first Managing Director was William Fraser of Pumpherston Oil. In 1924 Anglo Persian Oil supported the industry by opening the refinery in Grangemouth.

However, following the removal of wartime controls, soaring wage and price inflation made the oil produced in the Lothians more expensive and unprofitable. By 1932 the remaining shale oil companies were legally absorbed by Scottish Oils, which started to make dramatic cuts on staff and equipment. By 1938 there were five remaining crude oil works (Addiewell, Deans, Roman Camp, Hopetoun and Niddry Castle) and a dozen or so shale mines and pits, and a coal mine at Baads.

The Second World War bought an increase in oil prices and wages (the first real-terms increase since the early part of the century) and even the redevelopment of premises. However by 1954 shale oil had again become a loss-making industry in Scotland, and closures began from the 1950s onwards. Broxburn (closed in 1962) and Pumpherston (1964) were the last refineries to close.

Young’s … also developed Irano Products Ltd, a subsidiary chemical company, which was subsequently called BP Detergents Ltd (26/8/1958 – 6/11/1989). This company, not to be confused with BP Detergents International, was called Young’s Detergents Ltd from 1989 onwards.

1858 – Mineral Statistics of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland for 1858 – Boghead, Clay of coal measures. Name of freeholder – Duke of Hamilton. Name of manufacturer – James Young. Bricks manufactured. (Note – SBH – This entry may well refer to a different brickworks but I believe it will be the same ‘James Young’).

09/01/1869 – Glasgow Herald – To brickmakers. Contractors wanted to make and burn common brick at Addiewell Brickworks. Particulars can be had on application to Mr Scott, manager. Addiewell Chemical Works, West Calder. 06/01/1869.

1889 – 1910 – Lease agreement between Peter McLagan and Young’s Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company Limited – Commencing 11/11/1889 – Terminating 11/11/1910 – in part states … That is to say, the said Peter McLagan has let, and by these presents, in consideration of the tack duty and royalties and others, and under the conditions after mentioned, lets to the said Young’ Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company (Limited), incorporated as aforesaid, but excluding assignees of the said Company, whether legal or voluntary, and also excluding sub-tenants, unless approved of in writing by the said Peter McLagan or his successors, All and whole the bituminous or oil shales and coal and coal seams, ironstone, limestone, and common clay, and fire-clay declaring that the common clay and fire-clay hereby let shall only be used for the purpose of making bricks or drain tiles, but for no other purpose, except in so far as it may be found necessary to remove the same in working the other minerals hereby let, which clay so removed the said Company shall be entitled to deal with as they may think proper in that part of the first party’s estate, consisting of the farms of Forkneuck, Broadyetts, and Stankards, as far south as the Edinburgh and Batbgate Railway …

… The said Company bind and oblige themselves to erect and keep accurate steelyards and weighing machines at the mouths of each of the pits or other mineral workings, and to keep correct accounts of the quantity of shale sold or used, and of the oil and other products produced from the shale manufactured at their works as aforesaid, and of the coal, ironstone, limestone, and other minerals output, and of the bricks and drain tiles manufactured from the common clay and fire-clay let for that purpose, and to furnish to the proprietor or his agent if required …

1865 – Addiewell Oil Works – The (workmen’s) houses were built from Addiewell-made bricks. A clay pit was dug very close to the site – near the station – and the clay was made into bricks in a brickworks beside the clay pit.

16/05/1865 – The Scotsman – The shale district of West Calder … The new manufactory was being built on the estate of Addiewell … Mr Young addressed himself at the outset, a long row of neat brick cottages was erected without delay upon his own estate, and these have been given over to the skilled mechanics employed at the works. In addition to these, two rows of commodious wooden huts capable of accommodating about 130 men, have just been completed and taken possession of by the navvies. A good many cottages and houses have also been recently built at the village to meet the want that existed, and which promises to be soon renewed. Much time and expense will be saved in the erection of the new chemical works by the means that have been taken to procure a sufficient and constant supply of bricks. One of the fields in the immediate vicinity yields clay in large quantities; and on that bring discovered, Mr young immediately built a brickwork, which is at present in active operation. Steam machinery is used in one of the departments of this trade, and an apparatus is about to be fitted up to supersede the system of making bricks by hand. This machine is estimated to turn out thirty-five thousand bricks a day and will give facilities for keeping up a constant supply. The whole of the buildings will thus be constructed from bricks manufactured on the spot an arrangement which, besides being cheaper, will save endless carriage and carting. The brickwork will form a permanent part of the new establishment. In a huge chemical work like the one in process of formation, bricks are constantly in demand. The intense heat applied to the stills soon consumes the brickwork of the furnaces and necessitates their constant repair. The clay, accordingly, which is so abundant on the estate, will be put to a very useful purpose …

1866? – In fact, a new village had to be built. From the bed of clay and fireclay on the site at Addiewell the main raw materials came. A brickfield was begun and a highly mechanised brickworks built. One hundred and twenty new houses were built in the existing nucleus of West Calder; by March 1866 contracts had been placed for 300 more on land nearer the works; thus arose the new village of Addiewell (Page 298).

09/01/1869 – The Scotsman – To brickmakers and contractors. Wanted to make and burn common bricks at Addiewell Brickwork. Particulars can be had on application to Mr Scott, Manager. Addiewell Chemical Works, West Calder. 06/01/1869.

17/04/1876 – Edinburgh Evening News – While a bricklayer’s labourer named James Curran was working at the Brickworks, Addiewell on Saturday, he was knocked down by a truck which was coming up the line and ran over his right leg and hand and cut his head. He was conveyed to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary where it was found necessary to amputate two fingers of his right hand.

1879 – They purchased the West Calder Oil Works, including the workmen’s houses known as the Gavieside Hows (108 houses) and also their shale fields at South Cobbinshaw. Since then they have purchased a group of 59 houses at Cobbinshaw, which belonged to the Cobbinshaw Oil and Brickworks.

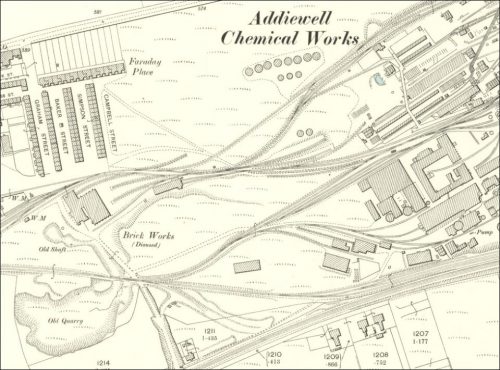

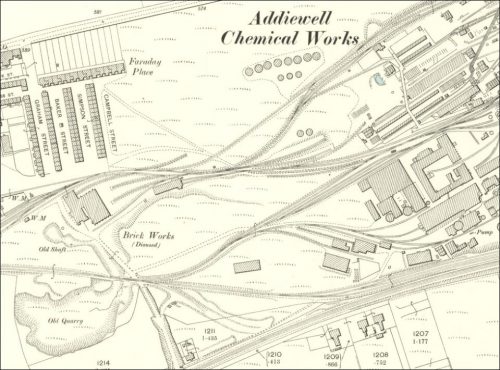

Below – 1895 – Addiewell Brickworks, Linlithgowshire – disused

1905 – OS Map describes the ‘old quarry’ on the above map just situated to the bottom left of the brickworks as an ‘old clay pit’

27/01/1911 – Midlothian Advertiser – Article on the golden wedding of Mr and Mrs John Paterson, Helenlea, West Calder … Mr Paterson was employed at the Addiewell Oil Works … the scarcity of houses led the oil company to erect houses for their workmen, Clyde Street, West Calder being one of the first blocks to be built. The clay which had been got at Westmuir Farm was not a success and teh company next started a brickwork at Addiewell and built the village with bricks of their own manufacture …

27/08/1926 – Montrose, Arbroath and Brechin Review – Local man’s coal saving device – A Canadian correspondent states that Mr David M. Duncan, a native of Bridge of Dun, has just patented a coal saving smoke consuming device for factory boilers, which is regarded as revolutionary and is highly praised by Canadian and American experts. Mr Duncan acts as Advisor to the Dominion Government, the Toronto City Council, and the Toronto School Board. Accompanied by Mrs Duncan, he is among the passengers on the Canadian Pacific liner Metagama, bound for Glasgow. He is well known in Scottish business circles, having some years ago organised brick Works at, among other places, Polmont, Addiewell. Whifflet and Coatbridge. He will spend a few weeks with his son-in-law. Mr John Forest, Ironmonger. Coatbridge.

13/03/1969 – Young’s paraffin light and mineral oil company limited – Report of the directors – in part states ” … All and Whole the bituminous or oil shales and the coal and coal seams, ironstone, limestone, and common clay, and fire-clay (declaring that the common clay and fire-clay hereby let shall only be used for the purpose of making bricks or drain tiles, but for no other purpose, except in so far as it may be found necessary to remove the same in working the other minerals hereby let, which clay so removed the said Company shall be entitled to deal with as they may think proper) in that part of the first party’s estate, consisting of the farms of Forkneuck, Broadyetts, and Stankards, as far south as the Edinburgh and Bathgate Railway … and … The said Company bind and oblige themselves to erect and keep accurate steelyards and weighing machines, machines at the mouths of each of the pits or other mineral workings, and to keep correct accounts of the quantity of shale sold or used, and of the oil and other products produced from the shale manufactured at their works as aforesaid, and of the coal, ironstone, limestone, and other minerals output, and of the bricks and drain tiles manufactured from the common clay and fire-clay let for that purpose …

**********************************

SCHEDULE to the Report of the Directors

1. Throughout the year the company operated detergent and wax manufacturing plants and a brickworks and there were no exports. lt is estimated that the three trades affected the profits to the following extent.

Detergents, Profit £100,953, Wax, Profit £34,028, and Bricks, loss £1,821.

********************************

The following extracts are from a thesis submitted in 1963 by John Butt entitled “James Young: Scottish industrialist and philanthropist”. Source

… The physical appearance of the first Bathgate coal oil plant is something of a mystery since there is no extant plan before 1868. However, from Youngs and Meldrums later statements and some contemporary evidence it is possible to build up a reasonable picture. Young estimated a weekly production which could be obtained from the through-put of six benches of retorts or about thirty retorts in all. These alone would cost, according to the advice given to Young, £60 per bench or a total of £360 for retorts. Young’s plant design was dominated by at least one large chimney to which the brick fire kilns were connected by flues – fire-bricks at 7/6d per hundred must have produced great additional capital costs. Above the three brick fire kilns rested the bench of five retorts laid out horizontally, three below and two above …

… Near the brick fire kilns would be the ordinary coal bunkers. One man would refuel the brick fire kilns and charge the five retorts in one bench. Each retort would normally hold up to 2 cwts. of coal and at the gas-works, it was normal to pack in as much coal as possible for this made the coke compact and cheaper to produce …

… This section of the plant would have been subject to heavy depreciation charges for the unprotected cast-iron would oxidate in the heat. To prevent this it was decided to brick that portion of the retort where the flame was most violent to prevent the iron from being burnt away …

… In August 1855 he tried a new fire-clay retort instead of the normal brick-encased cast-iron one, but the experiment was a failure since from the first the retort “seemed to be cracked” and then it exploded dangerously and was “rendered hopeless”…

… In fact, a new village had to be built. From the bed of clay and fireclay on the site at Addiewell the main raw materials came. A brickfield was begun and a highly mechanised brickworks built. One hundred and twenty new houses were built in the existing nucleus of West Calder; by March 1866 contracts had been placed for 300 more on land nearer the works; thus arose the new village of Addiewell …

… Young’s foundation of the oil-shale industry was a fortunate growth-point for the Scottish economy which set up a momentum of demand for a number of diverse industries: lamp making, chemicals, refining and retorting equipment, mining, quarrying and metallurgy, timber for casks, bricks and other building materials …

… The vertical retort, ten or more feet high, cased in brick to about five feet …

… after the oil vapour passed from the retort the door was opened and the exhausted charge withdrawn after the ash had been raked out. This took the form of a black, porous, poor quality coke about half the volume of the original charge. At first, its uses were limited. Gradually, instead of being sold merely for lime-burning, brick-making, and baking – or used in small quantities at the plant in the brick fire kilns, its uses were extended to welding iron, malting and grain drying, and brass smelting …

********************************

Now then – does an Addiewell brick exist?